Labour CND’s ‘Cutting Trident’ meeting in Parliament on 4th December saw the overwhelming case made for Labour to pledge its opposition to replacing the Trident nuclear weapon system at the next General Election and urged the party to open up to the debate in the coming months.

Addressing the meeting first was Nick Brown, former Chief Whip to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, said, ‘Labour can’t sit back and watch Coalition disagree on Trident – we need our own debate and clear position’. He argued that rather than waiting for reviews by other parties, Labour needs to debate Trident as soon as possible, including at the conference in 2013, then get out and explain it on the doors. He made clear his long-standing concerns about Trident had become outright opposition in the changed circumstances from when it was first commissioned.

Addressing the meeting first was Nick Brown, former Chief Whip to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, said, ‘Labour can’t sit back and watch Coalition disagree on Trident – we need our own debate and clear position’. He argued that rather than waiting for reviews by other parties, Labour needs to debate Trident as soon as possible, including at the conference in 2013, then get out and explain it on the doors. He made clear his long-standing concerns about Trident had become outright opposition in the changed circumstances from when it was first commissioned.

His key argument against replacement were the changed security circumstances, when Trident was conceived as a weapon to ‘flatten Moscow’ whereas the latest National Security Strategy made clear that the likelihood of state-on-state conflict was low and decreasing. But the economic circumstances compound the security case against Trident, and in particular the cuts to education that threaten the futures of young people today, should be reversed by transferring the funds allocated to Trident to lowering university fees.

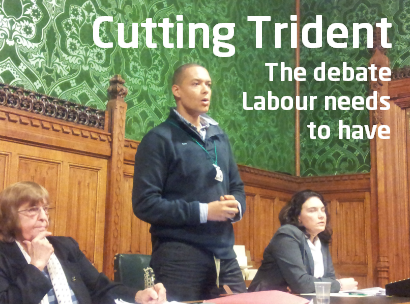

Clive Lewis, Labour’s candidate seeking to retake Charles Clarke’s old seat of Norwich South from the Lib Dems, spoke next and drew on his experience serving with the Territorial Army in Afghanistan in emphasising the security case against Trident replacement. In particular he said there was a strong military case with ‘conventional forces being hollowed out’ and listed the growing number of former senior officers who have condemned the allocation of funds to the submarine programme while conventional equipment ages. In his words, he said ‘I’d rather have more Chinooks than Trident’.

Clive Lewis, Labour’s candidate seeking to retake Charles Clarke’s old seat of Norwich South from the Lib Dems, spoke next and drew on his experience serving with the Territorial Army in Afghanistan in emphasising the security case against Trident replacement. In particular he said there was a strong military case with ‘conventional forces being hollowed out’ and listed the growing number of former senior officers who have condemned the allocation of funds to the submarine programme while conventional equipment ages. In his words, he said ‘I’d rather have more Chinooks than Trident’.

Katy Clark MP arrived fresh from voting against the Public Sector Pensions Bill and attacked the Tories for their public sector spending and welfare cuts while maintaining projects like Trident. She said the Labour Party needed to decide how it deals with Trident replacement in light of the attacks on living standards for ordinary voters and that, in that context, scrapping nuclear weapons would not be an electoral problem for the party. Addressing also the issue of Scottish independence, she said many in the Scottish Labour Party wanted to see Trident scrapped altogether, not just moved south, which was the risk of a yes vote in the Scottish separation referendum.

Katy Clark MP arrived fresh from voting against the Public Sector Pensions Bill and attacked the Tories for their public sector spending and welfare cuts while maintaining projects like Trident. She said the Labour Party needed to decide how it deals with Trident replacement in light of the attacks on living standards for ordinary voters and that, in that context, scrapping nuclear weapons would not be an electoral problem for the party. Addressing also the issue of Scottish independence, she said many in the Scottish Labour Party wanted to see Trident scrapped altogether, not just moved south, which was the risk of a yes vote in the Scottish separation referendum.

‘If Ed Miliband can be brave taking on Murdoch, he can be with Trident as well’, was National Policy Forum member Lucy Anderson’s view. On the party’s policy-making process, she said Labour should be talking to both the unions and employers about regional industrial strategies and the prospects for defence diversification. She said it was vital for Labour members to engage with the policy process, contributing directly to the Your Britain website – submitting proposals, voting on others and making comments – but also directly contacting NPF and NEC representatives.

‘If Ed Miliband can be brave taking on Murdoch, he can be with Trident as well’, was National Policy Forum member Lucy Anderson’s view. On the party’s policy-making process, she said Labour should be talking to both the unions and employers about regional industrial strategies and the prospects for defence diversification. She said it was vital for Labour members to engage with the policy process, contributing directly to the Your Britain website – submitting proposals, voting on others and making comments – but also directly contacting NPF and NEC representatives.

There was wide agreement that the party should urgently debate Trident this year – a number of activists expressed doubt that the party would have such a debate at the conference before an election – so a conference debate and vote in September 2013 is vital. Nick Brown appealed to trade unions to use their influence to facilitate that debate at the conference.

And in rounding up, Walter Wolfgang from the floor said ‘the country is fed up with the Tories but not yet convinced Labour has a progressive alternative’ and that ‘cutting Trident is essential to Labour’s credibility drive ahead of the next election’.

- Labour CND urges members to make a submission to the Your Britain website.

- You can vote and comment on and use this submission as a model.